ACROSS: It has been exactly one year since we last spoke. At that time, your company had recently rebranded from iMallinvest to ambas. What a turbulent year 2022 turned out to be for retail real estate investors! How did things go for you and the ambas team?

STEFFEN HOFMANN: First and foremost, I would like to congratulate the ACROSS team on your 15th

anniversary and to praise the range and coverage that your magazine has achieved as a cutting-edge

medium in the European retail real estate sector. Reinhard and all the people behind the magazine,

you have done an exceptionally good job! You guys have certainly brought this industry closer together. Now, back to your question: We have done well in these tough market conditions. The rebranding was successfully implemented. Thanks to some good media coverage, our clients and business partners quickly became accustomed to the new company name. While the overall investment market activity slowed down with the rapid increase in debt-finance rates during the second half of 2022, we supported our clients in the review of their strategic asset management options. For confidentiality reasons, I will not be able to comment on our transaction mandates at this stage. We are, however, working on some positive things.

ACROSS: In that case, let us discuss the historic evolution of the retail real estate industry from the perspective of the financial market. You started your career in the good old days of the European shopping center industry, back in 2000, and you have personally worked in eight different European markets since then. Reflecting a bit on the 15 years since ACROSS magazine launched in 2008, what foreseeable and unforeseeable events have influenced and changed the industry?

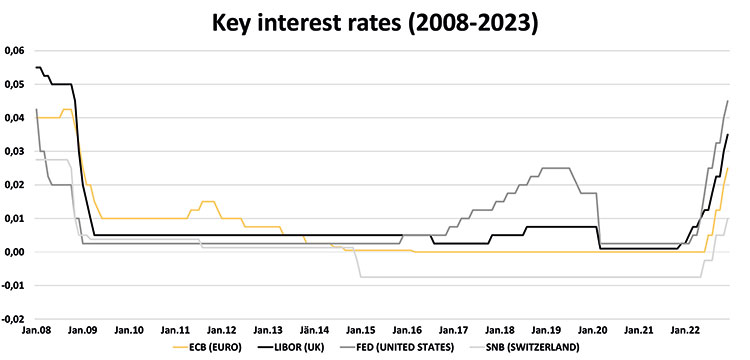

HOFMANN: Well, I guess we have to start with the Global Financial Crisis, the GFC, which triggered an enormous level of stress in the financial markets across the globe, including the real estate investment markets, between mid-2007 and early-2009. Most of your readers will forever remember it as the Lehman crisis. It was the perfect storm, and asset values dropped by the hour. Financial institutions went into panic mode. Across the globe, governments stepped in with all kinds of warranties and supported capital infusions into distressed systemically relevant lenders. Aiming to provide more liquidity to the market, the central banks at that time set the course towards a low-interest rate environment and carried out emergency actions that prevented the global financial systems from an immediate meltdown.

ACROSS: Did that have any direct and immediate impact on the retail real estate industry?

HOFMANN: Indeed, it did. After a period of strong risk-taking, the investor sentiment completely shifted. It would be an understatement to say that the risk-appetite of institutional investors was saturated for quite some time. I remember too well that some market-leading retail developers, who had built up impressive speculative development pipelines, suddenly found themselves in real trouble when it came to funding their projects. Lenders demanded more equity in the game. Global retail brands aborted their expansion programs and focused on their home markets. As a result, purchasers tried to back out of forward purchase agreements because the pre-agreed leasing conditions had not been met by the developers. Even highly experienced and formerly successful groups were forced to defer or cancel planned projects.

ACROSS: Was it the developers who got hit the hardest?

HOFMANN: Developers are brave people by virtue of their business model. They acquire risks that other market players expect to see cleared away before they buy into de-risked project situations. If such risks materialize unexpectedly and fast, it can be stressful. However, developers were not the only ones affected in those days. Institutional fund managers also tried to deleverage their vehicles, which required fresh equity injections from their underlying capital sources as lenders expected it. Open-ended fund vehicles with large diversified real estate portfolios had to limit their withdrawals. They could not sell their assets as quickly as people wanted to withdraw their money. In some cases, that triggered their statutory windup. It all happened in parallel – and very quickly.

ACROSS: What did financial investors learn from that experience?

HOFMANN: The investment procedures of institutional fund management platforms are now more rigorous. The excessive use of leverage is commonly restricted. Loan agreements foresee rigid covenants. Financial market regulators also put extensive reporting duties in place to monitor credit default risks. Asset managers today fill their dashboards with all kinds of operational KPIs to manage and control investment performance. If anything, the defensive components of the system have been strengthened. All that notwithstanding, markets still exaggerate as much in their downturns as in the better seasons. As we speak, the commercial real estate sector is experiencing a price correction across all sectors.

ACROSS: How did the shopping center asset class evolve in the years following the Lehman Brothers crisis?

HOFMANN: In most of the Western European legislations, the offshoots from the GFC heralded the end of the previous shopping center development era. It may have looked slightly different in some CEE countries, but most of the core real estate markets were saturated with newly built retail spaces. Investors’ interest shifted towards well-established standing assets with proven KPIs. Such retail assets had to be dominant in their catchment areas and had to allow for future asset management initiatives. International joint venture partnerships were formed on larger deals, and many prominent shopping centers traded between 2010 and 2016. The sector itself remained fairly popular until the effects of e-commerce technologies fed through in the retailers’ performance data.

ACROSS: What drove retail investment rationale outside of the large-scale shopping center sector during that period?

HOFMANN: Due to the lower interest-rate environment, certain investor groups raised their internal real estate allocation quotas. In doing so, those groups expressed a clear preference for steady income streams over speculative and more volatile development profits. The annual cash-on-cash return became more important than the targeted IRR of an investment, which may only be crystallized upon exit. Aiming to minimize occupier default risk, fund managers somewhat academically sought properties leased to tenants who had long leases and strong credit ratings. They wanted diversification of rental income streams and favored a geographical spread of portfolio risks over cluster risks. In other words, a small portfolio consisting of five assets with an average lot size of 50 million euros per property that generated an annual distribution yield of 4.5% with a projected IRR of 6.5% over the hold-period of an asset appeared more suitable to their search profile than owning a single asset with an asset value of 250 million euros that generated a distribution yield of 4.0% per annum and delivered a 7.0% IRR.

ACROSS: Where did investors find these criteria fulfilled?

HOFMANN: That specific search profile turned out to be the perfect description of groceryanchored retail warehouse properties and retail parks. In a way, a new asset class was defined, which subsequently experienced a 10-year boom period. In Germany, for example, the groceryanchored and more convenience-oriented retail park sector outpaced the fashion-oriented shopping center sector, in terms of total transaction volume, for the first time in 2014. Five years later, in 2019, transaction cap rates for such convenience-oriented retail formats fell below those of shopping centers, where deal pricing softened from 2017 on. In theory, city-centerbased department stores could have offered a similar return profile. However, the income stream would have depended on a single occupier, and various department store chains filed for insolvency protection during the GFC. The investment market in the years thereafter remained cautious in that respect.

ACROSS: How much of the described shift in investor preferences within the retail asset class can be attributed to structural changes in the occupier market?

HOFMANN: Comprehensive effects of rising e-commerce competition on tenant performance data in the traditional fashion industry broadly kicked in from about 2014 on. Online platforms succeeded in optimizing their infrastructures and constantly added to their market share. In response to that, physical space retailers started to push their e-commerce strategies. In continental Europe, occupancy-cost-ratios in fashiondominated retail assets started to look unhealthy from about 2016 onwards. Rent corrections at shopping centers were looming, which caused an outward yield-shift in the following years. Convenience-oriented retail formats and grocery stores continued to perform soundly.

ACROSS: Then, the markets were hit by COVID-19.

HOFMANN: Precisely! The unforeseeable outbreak of the pandemic in early 2020, with its social distancing requirements and strict lockdown orders for so called non-essential retail offerings, accelerated industry change. For cynics, that external shock in the real estate markets appeared to be a nail in the coffin of the shopping center sector – but it was not. It shook the industry heavily, however, and tested its breaking points. Some secondary malls may, indeed, never fully recover from it. The good news is that a considerable number of shopping centers also proved their resilience, and their KPIs bounced back in 2022. Consumers have returned to their centers and even seem to express a new preference for shopping experience in physical retail spaces. That also holds true for the likewise fashionoriented designer outlet mall sector, which performs remarkably well in many places.

ACROSS: Where will the inflationary tendencies that we all experienced in 2022 and the restrained lending market lead us in the next couple of years?

HOFMANN: It is another stress test. Indexlinked lease contracts, which are typical in retail real estate, should offer some important value protection for investors. High occupancy-costratios, in turn, may demand some form of compromise between landlords and their tenants. ESG initiatives will contribute to reduced energy consumption, which will help lower the overall service charge burden of retailers. Due to rising debt-finance costs and enhanced equity demand from lenders, a pricing correction in commercial real estate is progressing. Relative to other real estate asset classes, the retail sector looks attractive, though. Within retail, prime shopping center yields appear to be particularly interesting nowadays. Even with adjusted debt-finance rates, they still allow for positive leverage effects, which sets them apart from most of the other sectors. Notwithstanding that, their investor universe presumably remains smaller than in previous decades. Some large groups foresee allocations towards urban mixed-use properties instead – another new asset class that is currently being shaped in the hands of some brave developers.

Steffen Hofmann is Managing Partner at ambas